How I found faith in Bitcoin

- Oskar Volčanšek

- Oct 5, 2024

- 4 min read

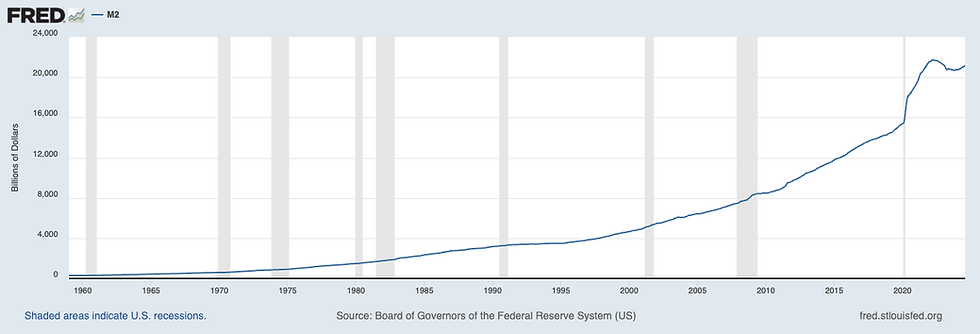

Since 1971, the money supply has increased by 5000%, with cumulative inflation over 600%. The debt of the United States federal government has increased by 9000%.

Is our money broken and is there an alternative for it?

What is money?

Before the invention of money, humans relied on bartering direct exchange of goods and services. While bartering works in small, close-knit communities where people trust one another, when trading more complex goods or goods with higher value it becomes hard to find a direct match of needs between two parties.

Imagine living in a village where you build furniture, and your neighbor grows food. You need vegetables, and your neighbor needs a new chair. It’s easy enough to exchange these items directly. This system works when needs align perfectly—a scenario economists call the "double coincidence of wants." But what happens if you need vegetables, and your neighbor already has enough chairs? Suddenly, the system breaks down.

To keep track of these exchanges, early societies developed an informal system called a ledger. In its simplest form, a ledger records transactions, debts, and credits between individuals. For instance, in our village example, if you give your neighbor a chair today but they don’t have any vegetables to offer right away, a debt is recorded. Your neighbor now owes you a favor or goods in the future. The community relies on trust, knowing that failure to repay this debt could damage your neighbor’s reputation, making future trades more difficult for them.

This system of trust can function effectively in small groups where relationships are personal and reputations are easily maintained.

However, when you want to trade with other communities, trust is not useful. You might need to trade with someone from a different village—someone you don’t know and trust. You have no way of guaranteeing they’ll honor their word, and they feel the same about you. In such cases, bartering and informal ledgers become impractical, this is where commodities as a form of money come into place.

Commodity as money

As humans started trading outside their communities, they needed something other than trust to make trading work. This is where commodities, 22started to function as an early form of money.

Rather than relying on a ledger to track who owes what, people began using tangible items that everyone valued as a medium of exchange.

Unlike bartering which depends on the needs of the moment, commodities like gold, silver, salt, or even grain carry inherent value. People knew these items were valuable, even if they didn’t need them right away.

Think of a farmer trading wheat with a blacksmith. If the blacksmith doesn’t need wheat but knows it can be easily traded with others, the farmer's wheat becomes valuable, not for its immediate use, but because it’s recognized as valuable in general. This transforms a commodity from a good for consumption into a medium of exchange.

What are the characteristics of good money? Money should be divisible, portable, durable, fungible, verifiable, and scarce. It can also have utility(but it is not necessary)

Divisible means that the money can be broken down into smaller units for various types of transactions.

Portable refers to the ease with which money can be transported across distances, packing a lot of value into a small, lightweight form.

Durable means that the money can be saved over time without rotting, rusting, or breaking down.

Fungible means that each unit is identical to another—one is as good as any other.

Verifiable means the money can be easily checked to confirm it’s real.

Scarce means that the money supply does not increase quickly.

Utility means that the money is intrinsically desirable in some way; it can be consumed or has aesthetic value, for example.

Throughout history, different societies used different commodities as a medium of exchange.

Shells

For thousands of years Shells were used as a form of money, for example, wampum a type of shell bead was used as money on the east coast of North America, there was a fixed exchange, between the shells and their coins, but as the industry progressed people were able to mass produce the wampum and it became worthless.

Tobacco

Tobacco was used as money in the American South, the problem with tobacco was that you could grow it, to counter, planters growing tobacco, the colonial government put restrictions on the amount of tobacco that could be grown. Another problem with tobacco is that there are various levels of tobacco and if all tobacco is valued at the same rate, quality tobacco is sold overseas while the lesser tobacco is sold domestically. In the end, tobacco too, could not withstand the technological evolution and was thus discarded.

How did gold win the commodity war?

Remember, before, when I listed the things that make money good, every other commodity only has 1, 2, or 3 of the listed quality for example tobacco, has utility and it is verifiable but, it's not fungible, scarce... Ultimately one commodity emerged as the global standard: gold.

Gold, on the other hand, has every quality of good money. It is divisible(to an extent, with silver handling smaller transactions). It's portable(small quantities of gold are very valuable, and thus a lot of value can be carried around easily), It is durable, fungible, and verifiable, it's scarce, because supply increases slowly, and in the end it has utility, it can be used for jewelry, decoration and today it's even used in computers.

The Birth of Fractional Reserve Banking

Before fractional reserve banking, banks were 100% asset-backed. People deposited their gold or other assets, and the bank issued paper claims against it, the bank didn't do anything with the deposits. Banks charged fees for keeping the assets. However, banks realized that not all customers withdrew their gold at the same time, allowing them to issue more receipts than the gold they held and in return, the depositors were spared of paying the fees for safekeeping.

Because banks competed against each other, each one trying to be the cheapest, gradually, only a fraction of the deposits were in the bank's vault.

This process creates more money in the economy than physically exists in reserves, fueling economic growth by expanding credit. However here a problem arises, what happens, if everyone wants their money at the same time, they cannot get it, and this creates bank runs, where too many depositors try to withdraw their funds at once, and the bank cannot meet the demand.

Free banking vs central banking

In a free banking system, banks issue their own notes, often backed by reserves like gold. There’s no central authority to regulate money creation—competition among banks maintains balance. Banks must manage their reserves well to retain public trust and prevent runs on their deposits.

Conversely, central banking places monetary control in the hands of a central authority, like the Federal Reserve. Central banks issue currency, set interest rates, and serve as lenders of last resort during crises .

In central banking systems, the central bank has a monopoly on issuing currency, providing a uniform money system. It can intervene in the economy by adjusting interest rates and conducting open market operations. Central banks also serve as a lender of last resort, providing liquidity to prevent bank failures and systemic crises, this encourages risk-taking because of bailout safety nets.

Base Money vs. Broad Money

In any economy, the money supply is categorized into different tiers, divided into base money and broad money.

Base Money is all the physical cash (coins and bills) and the money that banks hold in reserves at the central bank. The central bank has full control over how much base money exists. Think of it as the "seed money" from which all other forms of money grow.

Broad Money includes base money but also expands through bank lending. It’s the money you see in your checking and savings accounts. When banks make loans, they effectively create new money, adding to the broad money supply. This is the money that most of us interact with on a daily basis.

Speed of Transaction vs. Speed of Settlement

Speed of transaction refers to how quickly a payment or trade is initiated and processed. For example, when you swipe a credit card, the transaction happens almost instantly—your purchase is authorized, and the seller receives confirmation.

Speed of settlement, however, is how long it takes for the actual funds or assets to transfer and finalize. In financial markets, though you may buy a stock instantly, it could take a few days for the trade to settle. Similarly, when you make a credit card purchase, the actual transfer of funds between banks happens over a few days.

Throughout the story the Speed of transaction and settlement were the same, they were limited by how fast the information and things traveled, for example by foot, or by ship.

When the telegraph was invented transaction speeds greatly improved, allowing financial information to be sent almost instantly over long distances. Despite faster transactions, settlement times still lagged due to the physical transfer of money or assets. Nowadays, the speed of transactions is almost instant, but the speed of settlement is not.

The rise and fall of fiat money

Printing Money for War

Before the WW1 practically all money of major powers was backed by gold. The war needed tremendous resources, but the countries were not willing to finance the war through higher taxation, instead, they financed it through printing new currency. While this allowed governments to meet immediate funding needs, it led to inflation and currency devaluation, as seen with hyperinflation in Germany. At the same time, the winners experienced only very high inflation.

The Bretton Woods System and the Rise of the Petrodollar

After World War II, the Bretton Woods Agreement was created. Under Bretton Woods, the U.S. dollar was tied to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce, and other major currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar.

At the start it worked, until it didn't, foreign countries began demanding gold for their U.S. dollar reserves, putting pressure on the U.S. Treasury. In 1971, President Richard Nixon ended the dollar's convertibility to gold, effectively dending the Bretton Woods system and for the first time in history all major currencies were not backed by anything.

Following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the petrodollar system emerged. In the 1970s, the U.S. struck deals with oil-exporting countries like Saudi Arabia, ensuring that oil would be sold exclusively in U.S. dollars. In exchange, the U.S. provided military protection to key oil producers.

The petrodollar system increased demand for the U.S. dollar globally, allowing the U.S. to run large trade deficits while financing its spending through dollar creation. As a result, the U.S. could borrow cheaply, while countries dependent on oil trading had to store wealth in dollars, making them vulnerable to U.S. monetary policy shifts.

By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some.

-John Maynard Keynes

With money backed by nothing, governments can print ass much money as they want, the result is rising prices over time.

This inflation erodes the purchasing power of savings and wages.

Governments benefit from inflation. As the money loses value, the real value of government debt decreases, making it easier to pay off. If the government controls its own currency like the United States does, it can never default on its debt, because the Fed can just print more money. At what cost? At the cost of people's savings and purchasing power.

The most extreme cases of money printing can lead to hyperinflation, as seen in Zimbabwe or Venezuela, where the value of the currency plummeted to almost-worthlessness.

Even worse is that those who are close to the source of the money, benefit disproportionally more than those who receive, the money later,

This is called the Cantillon Effect, the cantollion effect, describes how newly created money benefits certain groups more than others. When governments or central banks inject new money into the economy, those closest to the source—typically governments, banks, and large corporations—gain access to it before prices rise. These entities can invest, expand, or pay down debt while prices remain relatively low. By the time the new money reaches the broader population, inflation has already set in, eroding purchasing power.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin is stateless money, it is not controlled by any government or central authority.

What is Bitcoin and How It Works

Bitcoin is peer to peer version of electronic cash that runs on a decentralized network known as the blockchain. Blockchain is a shared public ledger, maintained by a global network of computers (called nodes), every node has a copy of every transaction made in Bitcoin. Unlike fiat currencies, which can be printed, Bitcoin has a fixed supply of 21 million coins.

Mining is the process through which transactions are verified and added to the blockchain. Miners use powerful computers to solve complex mathematical problems; the first miner to solve the problem gets to add a new block to the blockchain and is rewarded with newly created Bitcoins.

Bitcoin functions using proof of work. This ensures that no single party can alter the transaction history or manipulate the currency. Transactions are verified by the network and added to the blockchain in "blocks," making it nearly impossible to alter past records without consensus from the majority of the network participants.

Privacy, Limited Supply, and Deflation

Bitcoin offers privacy in transactions, as users are identified only by their wallet addresses, not personal information. Although transactions are publicly visible on the blockchain, the identity behind the wallet is anonymous.

Unlike fiat currencies, which governments can print at will, Bitcoin's supply is capped at 21 million coins. This makes Bitcoin inherently deflationary.

How I found my faith in Bitcoin

As I have already established, from the point when Nixon took the dollar off the gold standard, money backed by gold became fiat money, backed by nothing, this gave the central bank power to print as much money as they wanted, new war, turn on the printer, recession on the horizon, turn on the printer, slowly the value of our money started losing value. Since 1971, the base money supply has increased by more than 50-fold, the broad money supply has increased by more than 35-fold, and cumulative inflation has been over 600%, although real inflation has probably been much higher. The debt of the United States federal government has increased by 90-fold.

I am confident to say something is not right.

Consumer Price Index for USA

Base Money Supply for the US

Broad Money Supply for the US

In addition;

I don't like the government's ever-increasing power to spy on every transaction I make.

I don't like inflation, and I don't like the government printing money and secretly taxing me through dilution, and then spending money for wars I don't support.

Bitcoin is a counterbalance to all of that, it is a stateless, private, and deflationary form of money. Bitcoin is divisible, each Bitcoin can be divided into 100,000,000 satoshis, it is portable, you only need a phone and the internet to use it, every coin is identical, Bitcoin is durable, verifiable, and the most important thing it is scarce.

At this stage, Bitcoin is not ready to become, the replacement for our current money, it is too volatile. As more people will hold and use Bitcoin, the market will become more stable, then will Bitocin become a feasible alternative to our fiat money.

My problem with Bitcoin is that I like what it offers, but I don't know what is the right price to pay for Bitcoin.

This blog was inspired by the book "Broken Money", written by Lyn Alden. In this Blog, I shared only a fraction of what is written in the book, and I would warmly encourage you to read it yourself.

Comments